Questionable Work Safety Data for Meat Processing Employees

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is responsible for ensuring food safety for all Americans. Meeting this obligation involves setting safety standards, such as controlling how food-source animals are fed and housed, the manner in which they are inspected and slaughtered, and how they are broken down, processed, and packaged.

The USDA is a vast system of 29 different agencies and employs around 100,000 employees. The food safety group’s mission is to make sure that meat, poultry, and eggs supplied to consumers are safe, wholesome, and properly packaged. Problems in meat processing can result in meat reaching the market that contains unacceptable levels of non-food contamination, such as tumors, hair, nails, bone, and feces. It can also be contaminated with foodborne bacteria.

Processing animals into food is a highly dangerous activity with many risks. Failure at any step can result in inferior or contaminated meat reaching the market. Animals can be too sick or injured to serve as safe food and must be culled from the processing line. Non-food parts must be safely and hygienically removed, and work surfaces must not harbor bacteria or waste. Failure in any step of meat processing can jeopardize the integrity of the food product and endanger the health of those consuming it.

Meatpacking involves an assembly-line of labor-intensive tasks that must be done correctly and in sequence to ensure a safe product. The animals must be inspected, and sick or diseased animals are not to be processed for meat. Carcasses must be inspected to ensure that they meet standards for quality. Once slaughtered, the carcass must be gutted, drained, and inedible portions are to be removed and discarded. This includes removal of meat that appears damaged or diseased.

Is Animal Processing Safe?

The Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) branch of the USDA requires inspections to be performed as per its regulations. In 2018, the agency proposed amendments to its rules on swine slaughtering, which is referred to as the New Swine Slaughter Inspection System (NSIS). The FSIS claims that the new rule, which revokes maximum line speeds, will improve the effectiveness of market hog slaughter inspection. This conclusion is counterintuitive and may simply be wrong.

The FSIS claims it is possible to revoke maximum line speeds by making changes that remove inappropriate meat before it reaches the processing line. The new rule also transfers food-safety tasks from federal inspectors to industry employees and reduces the number of USDA inspectors on slaughter lines. In some cases, the number of government inspectors is reduced by 40 percent.

The final rule was adopted in October 2019 and allows meat processing companies to use the new standards or continue operating under the old standard. Affected companies were required to report which standard they intend to use. Those not choosing the new standard will be held to the old standard.

Rulemaking Requirements May Not Have Been Met

Federal agencies must perform a cost-benefit analysis when adopting new rules or revising existing rules. The cost-benefit rational for the revisions was based on FSIS finding that work injury rates would likely be lower in plants using the new system. Since its publication, the NSIS rule has come under scrutiny. A report released by the Office of the Inspector General for the USDA found that the agency did not evaluate accuracy of worker safety data it used to ease limits on processing line speeds. In addition, the USDA was not transparent about the data it used in performing its worker safety analyses. These issues make it impossible to verify the integrity of the FSIS’s analyses.

There is good reason to believe that the data significantly underreported relevant workplace injuries. Some meatpacking workers reported being told that they will not receive light duty work if they report injuries. Others have been fired when they were injured and requested light duty. Some employers refuse to allow injured workers to go home after reporting injuries. They simply provide basic first aid and instruct them to return to work. Many immigrant workers are simply too afraid to report an injury.

What About Worker Safety Standards?

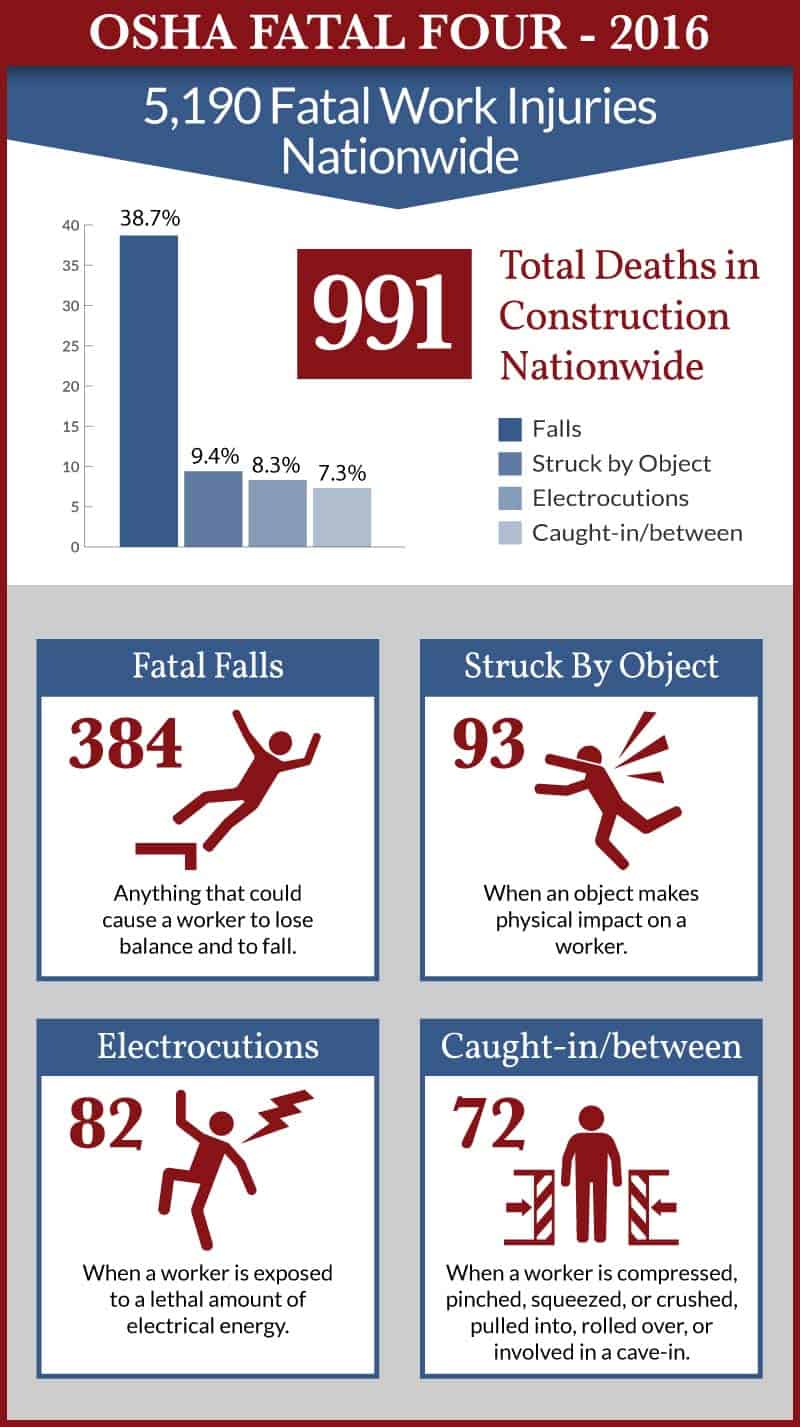

The USDA is not the only agency to regulate meat processing. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration also has jurisdiction over meat processing by setting standards for workplace safety. The goals of the agencies may differ; yet, oversight can enhance or diminish the critical mission and goals of the other agency. The USDA should not be revising standards in a way that would violate OSHA standards. This would create a murky situation where there is no clear guidance on what is permissible under the law.

Ergonomic Injuries

Ergonomic injuries are those related to body placement and use. They are caused by increased risk factors that render a person prone to injuries. The risk factors include repetitive motion, prolonged exposure to abnormal temperatures or vibration, prolonged awkward posture, forceful exertion, or pressure upon a particular body part. Typical ergonomic injuries involve a series of musculoskeletal disorders, such as Carpal Tunnel Disorder, tendonitis of the forearm or wrist, and shoulder disorders.

Meatpackers can experience ergonomic injuries since they stand at an assembly workstation and repeatedly perform the same movement during their entire shift. This arrangement is most likely to cause injuries as opposed to varying the activities over time. Speeding up the line is expected to increase the risk of injuries since there will be more repetitions of movement, which adds more strain.

OSHA has considered adopting an ergonomic-specific standard. Yet, the working conditions under which these injuries occur are so varied, it is difficult to state a specific standard with defined parameters. OSHA can issue ergonomic safety citations under the General Duty Clause, which states that each employer shall furnish a place of employment free from recognized hazards that cause or will likely cause death or serious physical harm to employees.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics maintains records of reported workplace injuries. Illness rates for meatpacking employees are 16 times higher than the average for other industries. It can hardly be questioned that the Department of Labor requires employers to track, record, and report workplace injuries. OSHA requests these records from worksites to provide significant evidence of a violation of the General Duty Clause where there is a risk of ergonomic injuries.

What Workplace Hazards are Present?

Meatpackers are exposed to a variety of workplace hazards. OSHA published guidelines to assist employees and employers in understanding the risks and precautions to take to avoid illnesses and injuries. Meat processing employees are uniquely exposed to biological agents that can cause health effects, such as skin infections, flus, and gastrointestinal infections, among others. Of particular concern is exposure to biological agents that are resistant to antibiotics, such as methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), which is very difficult to treat.

Additionally, many meat processing workers face exposure to the Coronavirus. To date, there is neither an effective treatment nor a vaccine available to address the virus. If an employee is injured or becomes sick at work, he or she is entitled to Workers’ Compensation. After seeking medical treatment, it is advisable to speak to a lawyer immediately to file a claim.

Bucks County Workers’ Compensation Lawyers at Freedman & Lorry, P.C. Help Injured Workers Obtain Compensation

If you have a work injury or illness, you are entitled to Workers’ Compensation. The legal process can be tricky and has some mandatory deadlines. If you file incorrectly or miss a deadline, then your right to compensation could be in jeopardy. One of our experienced Bucks County Workers’ Compensation lawyers at Freedman & Lorry, P.C. will evaluate your case and make sure it is handled competently. Contact us online or call us at 888-999-1962 for a free consultation. Located in Philadelphia, Cherry Hill, New Jersey, and Pinehurst, North Carolina, we serve clients throughout Pennsylvania.